Keeping Time

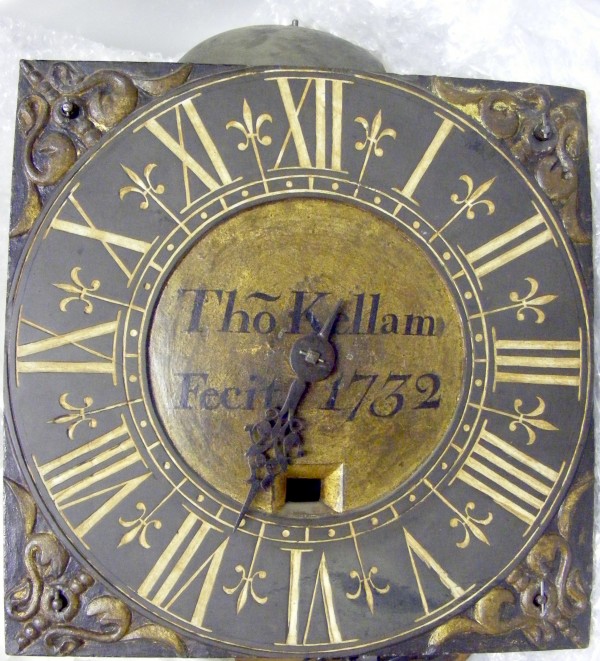

Long case clocks came into fashion in Leicestershire from about 1720 onwards. Then most locally made clocks would have 30 hour movements, which meant they needed winding up every day. Most London clocks had an eight-day mechanism, only needing to be wound once a week, and the best local clocks also worked like this. One of the earliest clocks in our collections is that made by Thomas Kellam in 1732, possibly in the village of Grimston. It has a pine case and a Swithland slate dial, and originally must have had a different movement with a pendulum of different length, because the insides of the case have been hollowed out to fit a standard pendulum.

At a time when watches were almost unknown, a portable sundial could give the owner a reasonable idea of the time on a sunny day. This one was made by Samuel Heyricke of Leicestershire in 1687, and judging by the pride he took in signing his name, he may also have made the mathematical calculations to design the dial in the first place.

The four sides and the top are painted to produce five dial segments, each of which had its own metal gnomon. The wooden peg on the bottom once fitted into a base or stand.

A bit more convenient than a sundial, pocket watches first appeared in the 16th century, but were expensive luxury items that only the very wealthy could afford to own. Local watchmakers started to manufacture them, until mass production took over and fashions changed. After the First World War, wrist watches became more popular.

A silver pocket watch Made by R Orson, a watchmaker in Melton Mowbray, hallmarked for 1856. The silver dial has raised gilt hour numerals, and a floral spray in relief in the centre. The back of the case is engraved with a central shield with the initials "GNW".

Wall Clock or "Tavern Clock", 1788

This clock was made in 1788 by Samuel Deacon at his workshop in Barton in the Beans. It has a simple 8-day movement (which needs winding up just once a week) which is inscribed “S.D. No 324, August 1788”. The clock was made for a public building, such as a chapel or tavern, and reflects the fact that, as the Industrial Revolution changed working lives in the 18th century, so it became increasingly important for people to know the time.

We are fortunate in that Deacon’s family continued the clockmaking business after his death until 1951. The contents of his workshop, with many of his original tools and work benches, and several clocks, are now in the County Council Museum collections, while his notebooks and business ledgers are in the Record Office in Wigston.